Interview

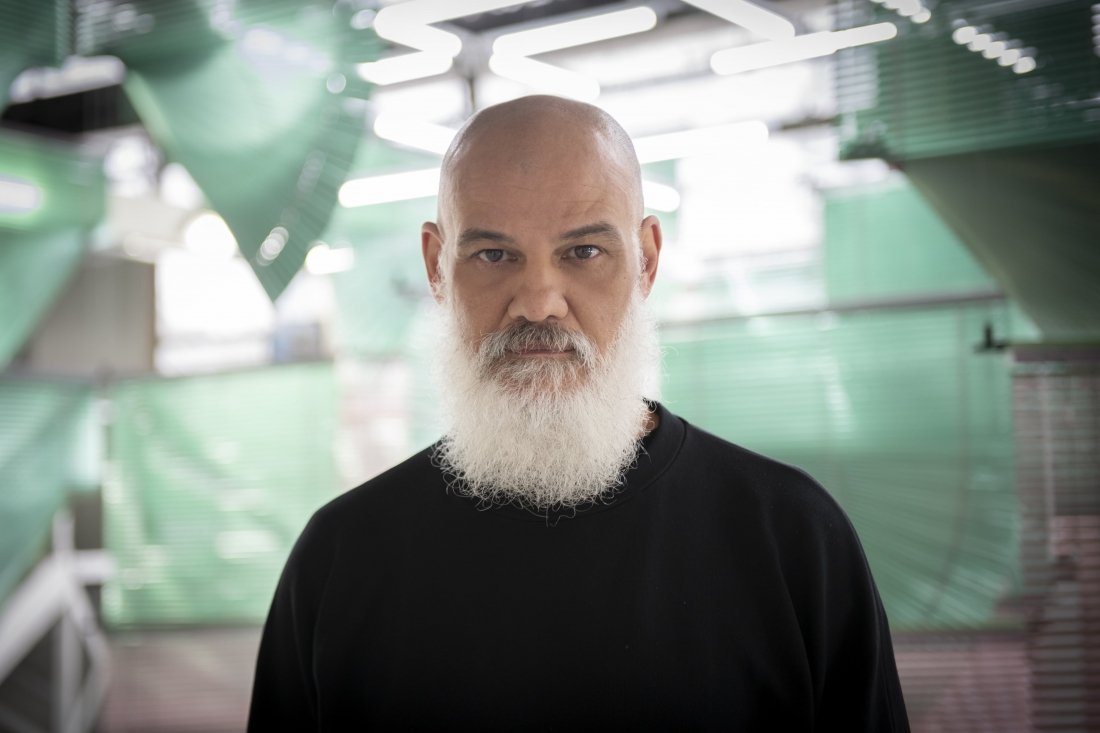

Marcelo Evelin

June

2022

Thu

2

The word uirapuru flies over this creation: it is the name of a bird that inhabits the Brazilian forests, is an indigenous legend, is the very title of the piece – which is presented, on June 3 and 4, at the Teatro Campo Alegre. How did you approach this multiplicity of the word throughout the research process?

The uirapuru is like word and as a bird... The idea of the bird has become almost a Brazilian cultural icon. In Brazil (and outside Brazil even more), we use to identify an exuberance, a type of Brazilianness. I was happy to call the piece Uirapuru because uirapuru is a word that comes from the Tupi-Guarani [linguistic family that encompasses several indigenous languages]. I liked not having a title in English (with what is customary in contemporary dance), but in Tupi-Guarani – which is a little spoken language, but that exists. In Brazil today, there are 186 languages and there are more than 300 indigenous ethnicgroups. There are 186 languages and we focus on speaking In English and French. The project began by calling the Povo da Mata [People of the Forest] and then I wanted to talk about the forest ... Not only of the ecological aspect of the Brazilian forest, not only of the Amazon, but about everything that inhabits the forests, all the kind of knowledge, subjective and poetic quality that exists in the Brazilian forest. The forest is dense, we don't know it. And for me, actually, that's what interests me: playing something I don't know. When I decide to do a piece, I don't make a piece about what I know, I always make a play about what I don't know. The uirapuru comes from a legend, from an impossible love. Two lovers fell in love and couldn't be together. And the warrior died of sorrow. I was very touched by the idea of someone dying of sadness for not getting a love. This notion of impossible love touches me a lot, because it seems that it is increasingly impossible for us to love each other. It's getting harder and harder for us to trust to turn themselves in. Because, to me, love is about total, savage, passionate delivery. This warrior died of love and was transformed into a bird by Tupã (God of Brazil). That bird started singing to this woman for the rest of her life and delighting the whole world. I really like that idea. I don't know if it's a gift or a torture for this Indian. Because, in fact, she's listening to that bird all the time, and remembering that love she couldn't have.

The uirapuru is a bird that is endangered in Brazil – like almost all brazilian people. We can practically consider that we are endangered... In the sense that we are living a kind of dictatorship of indifference, of contempt. Contempt for all that is ours, for all that is genuinely ours, for everything that arises from our Brazilianness. I love to think – supported even in what Luiz Antônio Simas says – that we can no longer say that we are Brazil. We have to rely on the idea of Brazilianness. Because the only thing that escapes this government is our Brazilianness, a profusion of images, the gestures of our culture. Brazil is transformed into not sure what, something far from what it is...

The uirapuru is a rare bird. I like the idea that it's a bird that barely appears, that it's a bird that asks anyone who hears it a certain kind of concentration. And then I start thinking about a choreography to listen to, a preparation to hear something. Not something I bring on stage, but something that is in the world and that seems that we do not have time to listen, that we are very worried about our phones, our Whatsapp, our Instagram. And then you can't even hear anything else, because it's all already given. For me, the uirapuru gathers all these things.

And it was also because of the idea of People of the Forest, that I abandoned this title, because this idea of identity is very complicated. Although it is important to think and approach the idea of identity in the world (mainly invisible identities), I am much more interested in differences and how we will negotiate these differences. For me, the fact that invisibilities become visible does not necessarily mean that visibility has to become invisible. It's not a reversal of value... It is something that I would like us to consider: that what is invisible, suppressed and repressed, not necessarily repressing anything, come to light. We stayed in this impasse with the idea of People of the Forest. I do not feel, for example, that I can talk about the Brazilian indigenous... Not only of the indigenous, but also of candomblé. The Afro-Brazilian religion is full of identities that inhabit the forests... The cablocos, which are very important entities in the ritual and for our understanding of what the world is. The bumba meu boi, for example, which is the most present folk manifestation in my state in Brazil, and that happens in the forest. It's the story of a charming ox that fled into the woods... And then a number of people (warriors, Indians, all people) have to be summoned to find this enchanted ox. Uirapuru also has this question of enchantment. Nowadays, a penalty of uirapuru is very expensive and is already on the black market. It has an omen quality, of bringing good luck. They say that anyone who sees a uirapuru sing has all the possibilities in life. So it has this enchanting, imaginative quality, which for me was very important in this project (and still is). Try to access something that's in your imagination. And the beautiful thing about imagination is the unsure. I'm much more focused on the unsures than on the certainties. We're used to having to be sure of things, to having to say things that we know. I'm much more interested in stating what I don't know, than in this ideological thing of everyone having to know everything, master everything, and be able to talk about everything.

A comparison is made between the extinction of uirapuru with the current contempt for Brazilianness. The synopsis of the piece tells us of "... a Brazil that, though shattered, still sings." This metaphor seems to carry a political and even activist connotation. Does the piece also manifest these themes? Or is it a more contemplative work, about liberation, about origins, about love?

My pieces are always political, but I hope they never seem political. In the sense of propaganda, of political gesture against or in favor of something. But I think dance itself is political because the body is political – especially in the moment we live. It's always political. I have this concern, it's something I have a conscience. But I try not to bring it up and explain it. It's a political piece, but I don't know if it's a contemplative piece. The word contemplative seems to me a lot like a piece to relax, to be well, to align the chakras. I'm not interested in that. I really like to give friction, to be there with people, to look in the eye, to propose. I don't mean by that I always want the fight, it's not that... I love being safe, being in love, being cool with mine. But we're not there much. When I say "a Brazil that, although broken, still sings," I don't need to explain what is destroyed in Brazil today. Anyone who saw last week's news (a person being asphyxiated inside a police car with everyone watching), knows that I can't talk about anything other than a broken country. About singing... I feel that our Brazilianness still sings. It's amazing the brightness in people's eyes in Brazil. It is impressive the condition of poverty, indifference and indifference that we live. But it is impressive to see that there is still love, that there is still affectation from one to the other, that there are still people who laugh. From the moment we started to structure the piece, when Fernanda Silva [performer] goes on stage gives a smile. And that's something that didn't turn into a scene – where I manipulated an performer to do it at the right time, because I wanted to get to a certain point... That's genuine of her. It is a person who comes from a very precarious place, is a Brazilian transsexual ... Brazil is the country that kills the most transsexuals in the world. Violence is here, not there. And Fernanda is the person who, during the process, always brought a smile. And that, to me, is very significant. And I think so, we keep singing. We are singing by being here, dealing with a whole bureaucratic issue (which is not ours), in which we have to negotiate... But we continue to believe in something, we can still produce a kind of subjectivity that, for me, is like singing.

In this process, I started studying birds a lot, read many authors, talked to many ornithologists, became very connected, saw a lot ... I realized that, for example, there is a French author who is called Vinciane Despert and who wrote a book called "Habiter en oiseau" (which means to inhabit a bird). It's a very strange title because it's "bird dwell" and not "dwell in a bird." It is said that birds sing, not to defend or mark a territory... They have no notion of property that we humans have. They are the territory, their song is what makes the territory, it is in itself the territory. I think that's very beautiful because singing is something that disappears, which, if we don't listen, doesn't even exist. Singing only exists when you listen.

After the premiere, a few days ago, in Teresina, Uirapuru is presented, for the first time, outside Brazil, in Porto. How do you describe your relationship with the city? There are already several works that you presented at the Teatro Municipal do Porto.

For me, it's a very happy coincidence. This piece has had several coincidences... It's funny because we're approaching this enchanting place, which isn't necessarily a mystical place. It's a place with another kind of logic, another kind of vibration. I started thinking a lot about how we make it vibrate... I am very tired of a certain intellectuality, of narratives that already say everything, of modernity, of important and great words that we use to communicate. I'm looking for the vibration that we're producing, how do we observe and perceive this vibration. So for me, it's a coincidence. It's the sixth work I've presented in Porto. I have a very close relationship with this city – it's the one I like the most in Europe. I'm not saying because I'm talking to you. (laughs) But really, it's the city I'm most interested in Europe. A few years ago, I almost moved here... I had been talking to Paulo Cunha e Silva, in doing a project here. But when he died, that connection stayed still, changed everything. It is now a very happy coincidence that this work is presented here.

The uirapuru is like word and as a bird... The idea of the bird has become almost a Brazilian cultural icon. In Brazil (and outside Brazil even more), we use to identify an exuberance, a type of Brazilianness. I was happy to call the piece Uirapuru because uirapuru is a word that comes from the Tupi-Guarani [linguistic family that encompasses several indigenous languages]. I liked not having a title in English (with what is customary in contemporary dance), but in Tupi-Guarani – which is a little spoken language, but that exists. In Brazil today, there are 186 languages and there are more than 300 indigenous ethnicgroups. There are 186 languages and we focus on speaking In English and French. The project began by calling the Povo da Mata [People of the Forest] and then I wanted to talk about the forest ... Not only of the ecological aspect of the Brazilian forest, not only of the Amazon, but about everything that inhabits the forests, all the kind of knowledge, subjective and poetic quality that exists in the Brazilian forest. The forest is dense, we don't know it. And for me, actually, that's what interests me: playing something I don't know. When I decide to do a piece, I don't make a piece about what I know, I always make a play about what I don't know. The uirapuru comes from a legend, from an impossible love. Two lovers fell in love and couldn't be together. And the warrior died of sorrow. I was very touched by the idea of someone dying of sadness for not getting a love. This notion of impossible love touches me a lot, because it seems that it is increasingly impossible for us to love each other. It's getting harder and harder for us to trust to turn themselves in. Because, to me, love is about total, savage, passionate delivery. This warrior died of love and was transformed into a bird by Tupã (God of Brazil). That bird started singing to this woman for the rest of her life and delighting the whole world. I really like that idea. I don't know if it's a gift or a torture for this Indian. Because, in fact, she's listening to that bird all the time, and remembering that love she couldn't have.

The uirapuru is a bird that is endangered in Brazil – like almost all brazilian people. We can practically consider that we are endangered... In the sense that we are living a kind of dictatorship of indifference, of contempt. Contempt for all that is ours, for all that is genuinely ours, for everything that arises from our Brazilianness. I love to think – supported even in what Luiz Antônio Simas says – that we can no longer say that we are Brazil. We have to rely on the idea of Brazilianness. Because the only thing that escapes this government is our Brazilianness, a profusion of images, the gestures of our culture. Brazil is transformed into not sure what, something far from what it is...

The uirapuru is a rare bird. I like the idea that it's a bird that barely appears, that it's a bird that asks anyone who hears it a certain kind of concentration. And then I start thinking about a choreography to listen to, a preparation to hear something. Not something I bring on stage, but something that is in the world and that seems that we do not have time to listen, that we are very worried about our phones, our Whatsapp, our Instagram. And then you can't even hear anything else, because it's all already given. For me, the uirapuru gathers all these things.

And it was also because of the idea of People of the Forest, that I abandoned this title, because this idea of identity is very complicated. Although it is important to think and approach the idea of identity in the world (mainly invisible identities), I am much more interested in differences and how we will negotiate these differences. For me, the fact that invisibilities become visible does not necessarily mean that visibility has to become invisible. It's not a reversal of value... It is something that I would like us to consider: that what is invisible, suppressed and repressed, not necessarily repressing anything, come to light. We stayed in this impasse with the idea of People of the Forest. I do not feel, for example, that I can talk about the Brazilian indigenous... Not only of the indigenous, but also of candomblé. The Afro-Brazilian religion is full of identities that inhabit the forests... The cablocos, which are very important entities in the ritual and for our understanding of what the world is. The bumba meu boi, for example, which is the most present folk manifestation in my state in Brazil, and that happens in the forest. It's the story of a charming ox that fled into the woods... And then a number of people (warriors, Indians, all people) have to be summoned to find this enchanted ox. Uirapuru also has this question of enchantment. Nowadays, a penalty of uirapuru is very expensive and is already on the black market. It has an omen quality, of bringing good luck. They say that anyone who sees a uirapuru sing has all the possibilities in life. So it has this enchanting, imaginative quality, which for me was very important in this project (and still is). Try to access something that's in your imagination. And the beautiful thing about imagination is the unsure. I'm much more focused on the unsures than on the certainties. We're used to having to be sure of things, to having to say things that we know. I'm much more interested in stating what I don't know, than in this ideological thing of everyone having to know everything, master everything, and be able to talk about everything.

A comparison is made between the extinction of uirapuru with the current contempt for Brazilianness. The synopsis of the piece tells us of "... a Brazil that, though shattered, still sings." This metaphor seems to carry a political and even activist connotation. Does the piece also manifest these themes? Or is it a more contemplative work, about liberation, about origins, about love?

My pieces are always political, but I hope they never seem political. In the sense of propaganda, of political gesture against or in favor of something. But I think dance itself is political because the body is political – especially in the moment we live. It's always political. I have this concern, it's something I have a conscience. But I try not to bring it up and explain it. It's a political piece, but I don't know if it's a contemplative piece. The word contemplative seems to me a lot like a piece to relax, to be well, to align the chakras. I'm not interested in that. I really like to give friction, to be there with people, to look in the eye, to propose. I don't mean by that I always want the fight, it's not that... I love being safe, being in love, being cool with mine. But we're not there much. When I say "a Brazil that, although broken, still sings," I don't need to explain what is destroyed in Brazil today. Anyone who saw last week's news (a person being asphyxiated inside a police car with everyone watching), knows that I can't talk about anything other than a broken country. About singing... I feel that our Brazilianness still sings. It's amazing the brightness in people's eyes in Brazil. It is impressive the condition of poverty, indifference and indifference that we live. But it is impressive to see that there is still love, that there is still affectation from one to the other, that there are still people who laugh. From the moment we started to structure the piece, when Fernanda Silva [performer] goes on stage gives a smile. And that's something that didn't turn into a scene – where I manipulated an performer to do it at the right time, because I wanted to get to a certain point... That's genuine of her. It is a person who comes from a very precarious place, is a Brazilian transsexual ... Brazil is the country that kills the most transsexuals in the world. Violence is here, not there. And Fernanda is the person who, during the process, always brought a smile. And that, to me, is very significant. And I think so, we keep singing. We are singing by being here, dealing with a whole bureaucratic issue (which is not ours), in which we have to negotiate... But we continue to believe in something, we can still produce a kind of subjectivity that, for me, is like singing.

In this process, I started studying birds a lot, read many authors, talked to many ornithologists, became very connected, saw a lot ... I realized that, for example, there is a French author who is called Vinciane Despert and who wrote a book called "Habiter en oiseau" (which means to inhabit a bird). It's a very strange title because it's "bird dwell" and not "dwell in a bird." It is said that birds sing, not to defend or mark a territory... They have no notion of property that we humans have. They are the territory, their song is what makes the territory, it is in itself the territory. I think that's very beautiful because singing is something that disappears, which, if we don't listen, doesn't even exist. Singing only exists when you listen.

After the premiere, a few days ago, in Teresina, Uirapuru is presented, for the first time, outside Brazil, in Porto. How do you describe your relationship with the city? There are already several works that you presented at the Teatro Municipal do Porto.

For me, it's a very happy coincidence. This piece has had several coincidences... It's funny because we're approaching this enchanting place, which isn't necessarily a mystical place. It's a place with another kind of logic, another kind of vibration. I started thinking a lot about how we make it vibrate... I am very tired of a certain intellectuality, of narratives that already say everything, of modernity, of important and great words that we use to communicate. I'm looking for the vibration that we're producing, how do we observe and perceive this vibration. So for me, it's a coincidence. It's the sixth work I've presented in Porto. I have a very close relationship with this city – it's the one I like the most in Europe. I'm not saying because I'm talking to you. (laughs) But really, it's the city I'm most interested in Europe. A few years ago, I almost moved here... I had been talking to Paulo Cunha e Silva, in doing a project here. But when he died, that connection stayed still, changed everything. It is now a very happy coincidence that this work is presented here.