Interview

Paulo Mota

November

2021

Wed

3

Director and actor of Buffalo Bill—the first performance of his newly created structure Devagar—, to be presented on November 5th and 6th, on the stage of the Grand Auditorium of Teatro Rivoli

Buffalo Bill is an icon of American culture. What led you to create this performance?

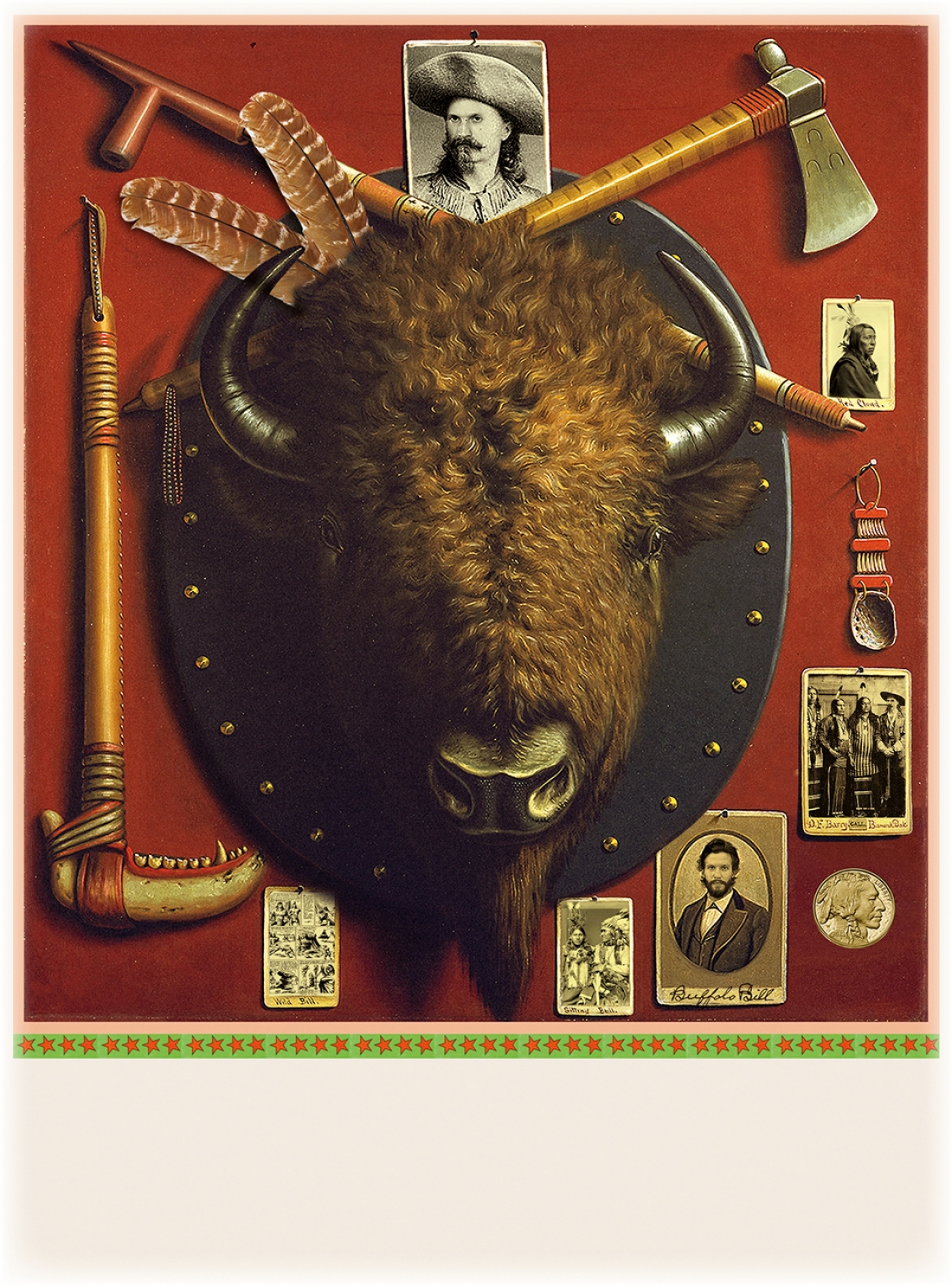

About three years ago, in conversation with my father, he commented that my grandfather told him something like: “It's not to read comic strips, it's to work”. I asked him what these stories were and he told me about Buffalo Bill. I went looking and found that there really was a person behind Buffalo Bill. His name was William Cody and he had a very private life. He was an American cavalry sniper, a businessman and ended up creating a circus with indigenous people, after having driven them out of the territory. In fact, this issue of the indigenous conflict in the United States of America immediately jumped to my attention.

On the other hand, I've been interested in working the language of comics and cartoons for a long time.

Then ideas started to multiply in my head and I decided to create this show.

Are we facing a biography of man beyond legend?

It is not a documentary work at all. The figure of Buffalo Bill is an excuse to talk about more current topics. As Walter Benjamin used to say, History is a sunflower that always turns to the present time. We look at Buffalo Bill so we can look at ourselves. There are several aspects that interested me; among them trying to understand what we inherited from the time of the industrial revolution, in which Buffalo Bill lived, and thinking about how we can position ourselves in this time, in which we live the digital revolution.

There is a possible parallel between comics and the digital world we live in: both are, or can be, forms of fiction.

Fiction is a very powerful weapon. The danger of digital, José Gil reminds him, is that it suddenly becomes the place where we choose to live. There are abstract zones that suddenly gain a space inside us and cease to exist in the concrete. Comics, on the other hand, have the smell of paper, have marks of the passage of time, have history, have the impression, keep us in physical contact.

What disturbs me is not the fiction—which is a great weapon to act on reality. What disturbs me is that we now exist 90% of the day in these digital places. We run the risk that our mental map may change and become more manipulable.

How did comics and the circus universe influence the creative process?

I like to work with some distance from reality, in the sense of the language code. I don't see myself in realism. The more I distance myself from reality, the more pleasure it gives me. At Devagar, we made a film entitled A Very Dangerous Game in which this distance was already happening. I think the same happens in this show. The language of the cartoon ends up lightening what is being said a little. There are even moments when it feels like we're seeing a show for childhood. There's a kind of horror movie idea, but it's comical and sometimes kind of childish.

There is simultaneously the language of the western and the archetype of the cowboy I'm playing with. We tried to bring the image of Buffalo Bill closer to the 50s and 60s comics. When we talk about this project to older people, over 60, they laugh with a good childhood memory.

The scenography and light work also have as references the western, the cartoon and the circus. This is because, strangely, Buffalo Bill ended up creating a circus with Indians—Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show—, which traveled around the world and showed the confrontations between Indians and Americans in a kind of reality show. In a way, it marked the birth of American pop culture.

Buffalo Bill is an icon of American culture. What led you to create this performance?

About three years ago, in conversation with my father, he commented that my grandfather told him something like: “It's not to read comic strips, it's to work”. I asked him what these stories were and he told me about Buffalo Bill. I went looking and found that there really was a person behind Buffalo Bill. His name was William Cody and he had a very private life. He was an American cavalry sniper, a businessman and ended up creating a circus with indigenous people, after having driven them out of the territory. In fact, this issue of the indigenous conflict in the United States of America immediately jumped to my attention.

On the other hand, I've been interested in working the language of comics and cartoons for a long time.

Then ideas started to multiply in my head and I decided to create this show.

Are we facing a biography of man beyond legend?

It is not a documentary work at all. The figure of Buffalo Bill is an excuse to talk about more current topics. As Walter Benjamin used to say, History is a sunflower that always turns to the present time. We look at Buffalo Bill so we can look at ourselves. There are several aspects that interested me; among them trying to understand what we inherited from the time of the industrial revolution, in which Buffalo Bill lived, and thinking about how we can position ourselves in this time, in which we live the digital revolution.

There is a possible parallel between comics and the digital world we live in: both are, or can be, forms of fiction.

Fiction is a very powerful weapon. The danger of digital, José Gil reminds him, is that it suddenly becomes the place where we choose to live. There are abstract zones that suddenly gain a space inside us and cease to exist in the concrete. Comics, on the other hand, have the smell of paper, have marks of the passage of time, have history, have the impression, keep us in physical contact.

What disturbs me is not the fiction—which is a great weapon to act on reality. What disturbs me is that we now exist 90% of the day in these digital places. We run the risk that our mental map may change and become more manipulable.

How did comics and the circus universe influence the creative process?

I like to work with some distance from reality, in the sense of the language code. I don't see myself in realism. The more I distance myself from reality, the more pleasure it gives me. At Devagar, we made a film entitled A Very Dangerous Game in which this distance was already happening. I think the same happens in this show. The language of the cartoon ends up lightening what is being said a little. There are even moments when it feels like we're seeing a show for childhood. There's a kind of horror movie idea, but it's comical and sometimes kind of childish.

There is simultaneously the language of the western and the archetype of the cowboy I'm playing with. We tried to bring the image of Buffalo Bill closer to the 50s and 60s comics. When we talk about this project to older people, over 60, they laugh with a good childhood memory.

The scenography and light work also have as references the western, the cartoon and the circus. This is because, strangely, Buffalo Bill ended up creating a circus with Indians—Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show—, which traveled around the world and showed the confrontations between Indians and Americans in a kind of reality show. In a way, it marked the birth of American pop culture.