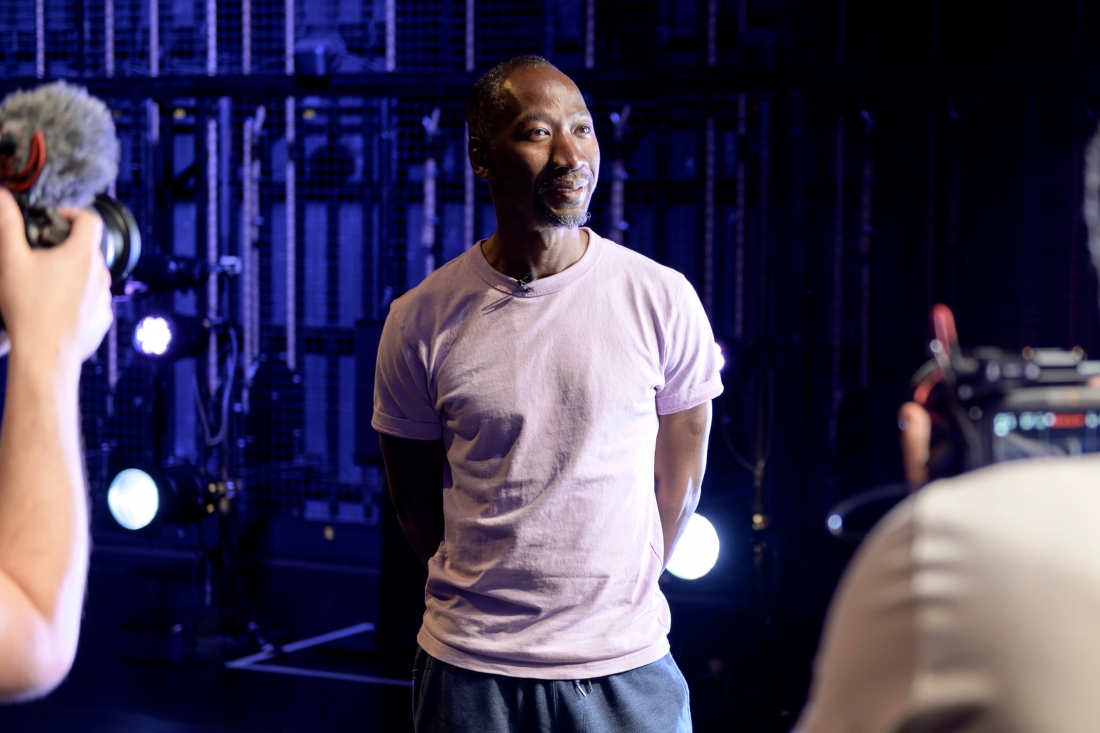

Interview

Amala Dianor

September

2022

Wed

7

On the 16th and 17th of September, the presentation of Via Injabulo by the South African dance company Via Katlehong opens the TMP’s 22/23 season. During their residency, in June, at Campo Alegre, we talked with Amala Dianor about Emaphakathini (one of the two pieces that are part of the show).

How did Via Katlehong's invitation come about? Have you ever worked or knew the company's work? How is the process of creating Emaphakathini going?

First of all, I’m very glad that the company invited me to work as a choreographer on this Via Katlehong project. It is a well-known company in France. I've been following them for over 10 years. Their first show marked me a lot. Generally, we [the artists] are very sensitive to everything that goes on in dance outside France. They have a very strong energy and a very unique dance. In South African dances we have the pantsula, the gumboot. I come from ip hop culture. We had the house dance, and now the pantsula. That's also what interested me in this collaboration, interrogating a little the dancers and the songs they currently use.

How did you cross your work references with the very specific features of Pantsula?

Starting from the dance that was proposed to me to work with, the singular pantsula, I was interested in knowing how the group would reveal itself within the movement. The movement was just a pretext to unravel as individuals. And above all, as individuals within a group. Basically, the work consists of freeing the individual, so that it can be revealed through dance. In this way, they move away from the formal structure of interpretation, from performing a choreography. And they can generate another form of communication, interaction with each other, and also with the public.

Dance is a fundamental element for the construction of a collective identity. How would you describe the importance of pantsula in the South African social context?

When I was invited to do this creation it was my first time in South Africa. I didn't know what to expect. From France, I knew that there had been Apartheid, the various variants of Covid-19, the World Cup, and other events. But for me, this country was a distant reality. I tried to imagine what this post-Apartheid generation would be like. What generation is this of South African artists? Where are they? Are they across borders? Or are they somewhere between two worlds that make them what they are, being more at one extreme than another? I was very curious to know the reality of this youth. When I started the creation I was in total immersion, welcomed by the artistic directors of the company, Steven Faleni and Buru Mohlabane. It was interesting because, suddenly, I was immersed in their realities, in their rhythms of life. I felt the pulses that made me understand that they are still, in a way, in a research process. And that is what interests me as a choreographer.

How did Via Katlehong's invitation come about? Have you ever worked or knew the company's work? How is the process of creating Emaphakathini going?

First of all, I’m very glad that the company invited me to work as a choreographer on this Via Katlehong project. It is a well-known company in France. I've been following them for over 10 years. Their first show marked me a lot. Generally, we [the artists] are very sensitive to everything that goes on in dance outside France. They have a very strong energy and a very unique dance. In South African dances we have the pantsula, the gumboot. I come from ip hop culture. We had the house dance, and now the pantsula. That's also what interested me in this collaboration, interrogating a little the dancers and the songs they currently use.

How did you cross your work references with the very specific features of Pantsula?

Starting from the dance that was proposed to me to work with, the singular pantsula, I was interested in knowing how the group would reveal itself within the movement. The movement was just a pretext to unravel as individuals. And above all, as individuals within a group. Basically, the work consists of freeing the individual, so that it can be revealed through dance. In this way, they move away from the formal structure of interpretation, from performing a choreography. And they can generate another form of communication, interaction with each other, and also with the public.

Dance is a fundamental element for the construction of a collective identity. How would you describe the importance of pantsula in the South African social context?

When I was invited to do this creation it was my first time in South Africa. I didn't know what to expect. From France, I knew that there had been Apartheid, the various variants of Covid-19, the World Cup, and other events. But for me, this country was a distant reality. I tried to imagine what this post-Apartheid generation would be like. What generation is this of South African artists? Where are they? Are they across borders? Or are they somewhere between two worlds that make them what they are, being more at one extreme than another? I was very curious to know the reality of this youth. When I started the creation I was in total immersion, welcomed by the artistic directors of the company, Steven Faleni and Buru Mohlabane. It was interesting because, suddenly, I was immersed in their realities, in their rhythms of life. I felt the pulses that made me understand that they are still, in a way, in a research process. And that is what interests me as a choreographer.